Analemmatic dials

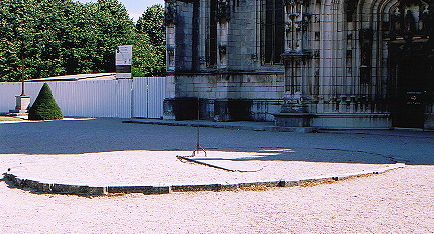

Brou (near Bourg-en-Bresse, Ain, France)

It really felt as a pilgrimage, the trip to this down-to-earth object: finally face to face with the archetype, the ancestor of all analemmatic sundials!

And how lucky were we: the sun was shining! Just to disclose that the dial was in the shadow of the church and would stay so for a while. No problem, we didn't mind. Around 11 o'clock the dial caught the sun.

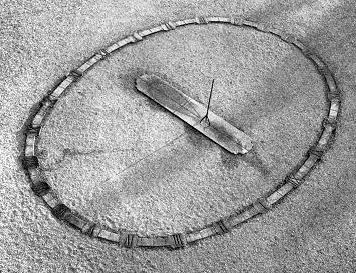

The major axis of the ellipse is 11.5 m, quite a generous size. The perimeter consists of a ring of tiles. All 24 hour points are present, twice ranging from I to XII. They read local time. The strips between the hour tiles have half-hour marks and shorter quarter marks. Detail: the 4 hr mark is given as IV, not as IIII (cf. the page on the four o'clock problem).

The date line has been engraved into a large slab of stone, with an analemma around it. Alongside the line are the initials of the months, without marks. Marks are present on the analemma: the first day of each month is marked by a small circle. The month is divided in 10-day units and subdivided per 5 days.

The date line has been engraved into a large slab of stone, with an analemma around it. Alongside the line are the initials of the months, without marks. Marks are present on the analemma: the first day of each month is marked by a small circle. The month is divided in 10-day units and subdivided per 5 days.

An iron rod on a tripod serves as the gnomon. Its height is 1.90 m (6' 3"). It is chained to the base plate, with enough slack to cover the entire date line.

The church has been built between 1513 and 1532, that is, within 20 years. Quite an achievement! Tradition has it that the sundial is from that era. It would have served as some kind of time clock, to prevent the workers from leaving early. In that case it was no problem to have it working only in the afternoon...

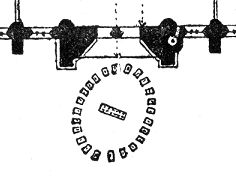

The sundial suffered from the traffic, which urged the astronomer Lalande to have it renovated out of his own pocket in 1756, and relocated to a spot right in front of the portal (see the figure at right). One may assume that the worshippers normally used a side entrance.

The sundial suffered from the traffic, which urged the astronomer Lalande to have it renovated out of his own pocket in 1756, and relocated to a spot right in front of the portal (see the figure at right). One may assume that the worshippers normally used a side entrance.

As the church deteriorated in the 19th century, the dial was threatened by debris falling down. It was restored again in 1902 and moved to the present location. The analemma was added at that occasion.

This object is the ancestor of all analemmatic dials. It nevertheless deviates notably from most successors at three points: the complete ring of hour points, the movable gnomon and the analemma. I will discuss these points briefly.

At this latitude hour points from 4 am to 8 pm would suffice. Perhaps aesthetic reasons led to the inclusion of the remaining hours. And indeed, the closed ring of hour points has something to it, don't you think? The picture here is from the booklet by Terpstra. North is at the upper left.

At this latitude hour points from 4 am to 8 pm would suffice. Perhaps aesthetic reasons led to the inclusion of the remaining hours. And indeed, the closed ring of hour points has something to it, don't you think? The picture here is from the booklet by Terpstra. North is at the upper left.

In this region, I found a number of other dials having 24 hour points: Gray, Besançon and Dijon.

To me, the appeal of the analemmatic dial is the human serving as gnomon, making it into an interactive instrument. A thin gnomon would improve accuracy, although most analemmatic dials are so large that the shadow does not reach the edge anyway. Pressing your hands together above your head also makes a thin gnomon, even longer than the rod here. Even then you would have to extrapolate your shadow.

An advantage of the rod may be that it attracts at least some attention. Otherwise most visitors would walk right past the dial. Even now many passers-by give it merely a brief glance. No information panel challenges parents to add to their kids' cultural education. Also the leaflets which are for sale at the entrance booth do not mention the instrument.

The only other dial I know of that has a movable rod as a gnomon is the one in Longwood Gardens.

To convert local time into civil time one needs to know (among other things) the equation of time for that day. Often, the EoT is provided in a table or graph at or near the dial. In case of an analemmatic dial, it is of course tempting to apply the correction by stepping aside from the date line when the sun is fast or slow with respect to mean time. That may be the idea behind the analemma here.

However, in this case the correction would be too large around noon, maybe close in mid-morning and mid-afternoon, depending on the time of year, and much too small or even reversed in early morning and late afternoon.

The gnomon thus has to be placed on the date line and not on the analemma. Unfortunately, most visitors do otherwise, being put on the wrong track by the fine-grain scale of dates present along the analemma.

Location: 46.2° N, 5.2° E

The construction of the convent and the church was commissioned by Margaret of Austria (1480-1530). She was the daughter of Maximilian, Emperor of Austria and Mary of Burgundy. In 1501 Margaret married Philibert II, Duke of Savoy, nicknamed Philibert the Fair, the son of Philip of Savoy and Margaret of Bourbon. Unfortunately, three years later young Philibert died of the complications of a cold, caught during a hunting party.

In order to create an appropriate memorial for her bewailed Philibert, Margaret commanded the construction of a new convent and church to replace the existing convent in Brou. It would also fulfill the vow her mother-in-law made in 1480 as her husband was ill, but which had not yet been kept when she died in 1483. And it should be said, young Margaret pushed ahead: the renovation of the convent started in 1506. Work on the church did not start until 1513, due to problems with the contractors.

In 1506 Margaret's brother Philip the Fair died, who was governor of the Netherlands. Daddy Maximilian appointed Margaret as Philip's successor and also as tutor of her nephew, the future Emperor Charles V (1500-1558). She had to move to Mechlin, then the governmental seat of the Low Countries. From there she closely supervised the construction work of the church in Brou, having appointed the Flemish master builder Loys van Boghum (also called Lodewijk van Bodeghem) as the architect. She would, however, never return to Brou and hence, never saw the church. She died in 1530 and was buried in Brou in 1532, together with Philibert and her mother-in-law.

The church is a real reliquary of worked stone, as the travel guide justly states. The three magnificent tombs, the beautiful stained glass windows and the choir screen (jube) are the most important sights of this church, which attracts lots of tourists.