Equatorial dials

Roussillon (Vaucluse, France)

This huge equatorial dial is set on top of an ochre rock, near the village and across from the cemetery. It measures 3 m (10 ft) in diameter. The wire that forms the pole-style has a white bead as an index. The cylindrical dial face is rather wide. One might therefore also call this a polar dial. The SAF catalogue calls it a cadran cylindrique polaire.

The top of the dial face is much narrower than the bottom. This is functional: the days last shorter in winter than in summer, 8½ hours minimum vs. 15½ hours maximum. It also avoids nasty shadows on the dial in early morning and evening hours in the summer.

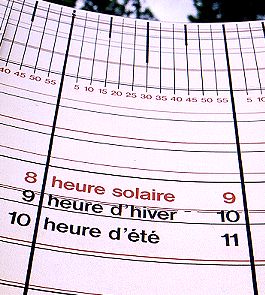

The line pattern is quite elaborate. Vertical hour lines, divided in 5 minute ticks along top and bottom. The quarter and half-hour lines have been accentuated. The hour lines have been labeled by civil and daylight saving time (in black) and local time (in red). Don't local and civil time differ by less than an hour? you asked correctly. Yes, the difference is here 39 minutes on average. I'll return to that below.

The line pattern is quite elaborate. Vertical hour lines, divided in 5 minute ticks along top and bottom. The quarter and half-hour lines have been accentuated. The hour lines have been labeled by civil and daylight saving time (in black) and local time (in red). Don't local and civil time differ by less than an hour? you asked correctly. Yes, the difference is here 39 minutes on average. I'll return to that below.

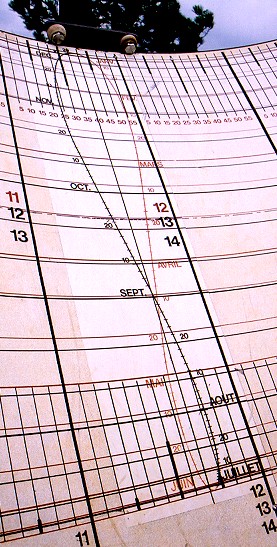

An analemma is drawn in the center, around the 12.40 hour line, with 2-day divisions. The first half-year (growing days) is in red, the last half in black. Date lines are indicated for the first, 10th and 20th day of each month, also in red or black. The equinoxes are marked by a dashed black line at September 23.

An analemma is drawn in the center, around the 12.40 hour line, with 2-day divisions. The first half-year (growing days) is in red, the last half in black. Date lines are indicated for the first, 10th and 20th day of each month, also in red or black. The equinoxes are marked by a dashed black line at September 23.

How to read the time accurately from this device? Such a giant should be able to yield a precise reading anyway.

Usually, one of two methods is used. Either the dial reads local apparent time, and one should apply corrections for the time zone and the equation of time, or the correction for the time zone has already been applied (for regular or DST, as desired) and one only has to correct for the EoT.

In the first case, the 12 hr line should be in the north-south plane, which is not true here. In the second case, 12:39 should be in the north-south plane, which is also not found here.

I assume that the time scale is adjustable here. It should be rotated until the north-south plane intersects the analemma just at the present date. Then the correct civil time can be read directly (regular or DST, as desired).

We visited here on July 23, when the EoT is -6 minutes, so the sun's azimuth is due south at 12:45. And that is just about the time you see below the center of the arch that supports the pole style. (The analemma reads 12:47 at this date; a matter of rounding, for sure).

The base of the dial is indeed provided with adjusting screws. The silver one protrudes for another 20 cm (8") or so at the other side and thus has a considerable range.

The base of the dial is indeed provided with adjusting screws. The silver one protrudes for another 20 cm (8") or so at the other side and thus has a considerable range.

In my mind's eye, then, a city official daily ascends the hill in his service truck to adjust the time scale. The analemma, then, is there solely for him and not for the visitors, because they don't need it.

The plaque at the base names the designer/builder: Jean Raffegeau, 1923-1993.

For those purists who desire a reading of local time, the time scale can be rotated even further, so that the hour line labeled '12' in red is just in the north-south plane.

Location: 43.9° N, 5.3° E

Design: Jean Raffegeau

Inauguration: 1923?

Roussillon is also the name of a region in the eastern Pyrenees, at the French-Spanish border. It has nothing to do with this tourist center, however, which is set on a ridge in the Provence, some 40 km (25 miles) east of Avignon.

Roussillon is also the name of a region in the eastern Pyrenees, at the French-Spanish border. It has nothing to do with this tourist center, however, which is set on a ridge in the Provence, some 40 km (25 miles) east of Avignon.

On a walk through the city you may discover several old sundials, like the one here on the bell tower, which lost its polestyle. And a lot of new ones, to be taken home as a souvenir...

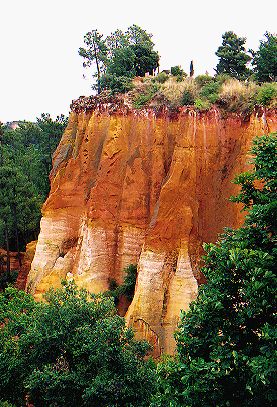

The region around Roussillon is noted for its ochre soil. The dial site has a number of boards explaining the geological origin of this soil and recounting the history of the ochre industry that once flourished here.

The region around Roussillon is noted for its ochre soil. The dial site has a number of boards explaining the geological origin of this soil and recounting the history of the ochre industry that once flourished here.